R Basics

Clarke Iakovakis

Binder link to this notebook:

https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/ciakovx/ciakovx.github.io/master?filepath=RBasics.ipynb

Please note the Binder link is condensed and modified for the Jupyter Notebooks environment, whereas this page is longer and pertains to the R Studio environment.

Introduction

This guide accompanies the first day of instruction for our course at the 2021 FORCE11 Scholarly Communications Institute: “W25 - Working with Scholarly Literature in R: Pulling, Wrangling, Cleaning, and Analyzing Structured Bibliographic Metadata.”. It covers basic nuts and bolts of using R.

This walkthrough is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

Writing & Evaluating Expressions

The prompt is the blinking cursor in the console pane prompting you to take action, in the lower-left corner of R Studio. We type expressions into the prompt, and press the Enter key to evaluate those expressions.

You can also use R like a calculator, as you saw in the previous set of exercises.

2 + 2

## [1] 4You can perform all kinds of mathematical operations using R, but we will not be covering that in our session today.

Assigning values

The first operator you’re going to come across is the assignment operator. This is the angle bracket (AKA the “less than”" symbol): <, which you’ll get by pressing Shift + comma and the hyphen - which is located next to the zero key. There is no space between them, and it is designed to look like a left pointing arrow <-.

# assign 5 to y by typing this in the console and pressing Enter

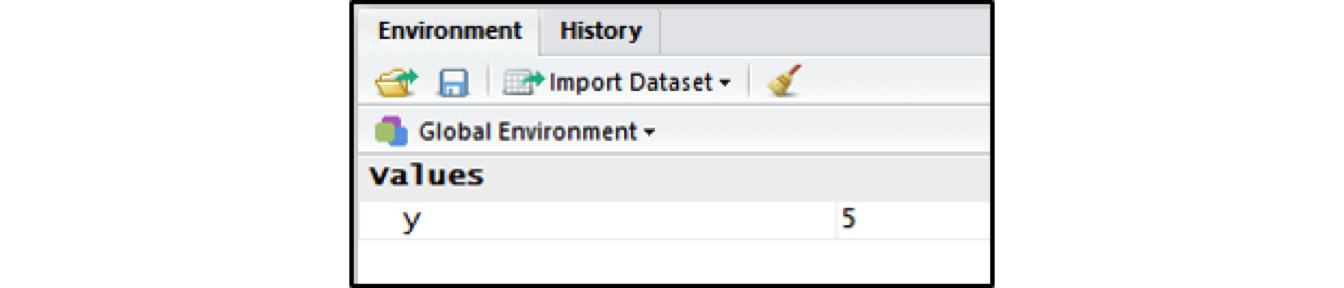

y <- 5Here I am creating a symbol called y and I’m assigning it the numeric value 5. Some R users would say “y gets 5.” Lowercase y, is now a numeric vector with one element. Or you could say y is a numeric vector, and the first element is the number 5. When you assign something to a symbol, nothing happens in the console, but in the Environment pane in the upper right, you will notice a new object, y.

Evaluating Expressions

If you now type y into the console, and press Enter on your keyboard, R will evaluate the expression. In this case, R will print the elements that are assigned to y (the number 5). We can do this easily since y only has one element, but if you do this with a large dataset loaded into R, it will obliterate your console because it will print the entire thing. The [1] indicates that the number 5 is the first element of this vector.

# evaluate y

y

## [1] 5

# you can also use the print() function

print(y)

## [1] 5Note that you can type comments into your code by using the hash symbol #. Anything following the hash symbol will not be evaluated. Comments are essential to helping you remember what your code does, and explaining it to others. Commenting code, along with documenting how data is collected and explaining what each variable represents, is essential to reproducibile research.

# add 20 to y

y + 20

## [1] 25You can assign anything to any variable, and then perform operations on or with that variable. Try typing in the expression y + 20 and press enter. R prints the number 25 to the console.

TRY IT YOURSELF

- Make sure that 5 is assigned to

yby typing iny <- 5 - Assign the number 10 to variable

x. Addxandyand evaluate the expression. - Assign

x + yto variablemyTotal. Look in the Environment pane to see whatmyTotalcontains. - Run

View(myTotal)to see it in the Data Viewer

Tips for assigning values

- Do not use names of functions that already exist in R: The assignment operator assigns a value to a symbol. We can pretty much pick any symbol, or name, for that variable, as long as it is not already a function in R. For example, you wouldn’t want to name a variable

sumbecause if you might end up in a confusing situation writingsum(sum) - R is case sensitive: It is important to note that R is case sensitive. If you try evaluating a capital

Y, you will be toldError in eval(expr, envir, enclos): object 'Y' not found. - No blank spaces or symbols other than underscores: R users get around this in a couple of ways, either through capitalization (e.g.

myData) or underscores (e.g.my_data). - Do not begin with numbers or symbols: Try to evaluate

1z <- 4or%z <- 4and read the error message. - Be descriptive, but make your variable names short: It’s good practice to be descriptive with your variable names. If you’re loading in a lot of data, choosing

myDataorxas a name may not be as helpful as, say,ebookUsage. Finally, keep your variable names short, since you will likely be typing them in frequently.

Calling a function

R is a “functional programming language,” meaning it contains a number of functions you use to do something with your data. Call a function on a variable by entering the function into the console, followed by parentheses and the variables. For example, if you want to take the sum of 3 and 4, you can type in sum(3, 4).

Function arguments

Typing a question mark before a function will pull the help page up in the Navigation Pane in the lower right. Type ?sum to view the help page for the sum function. You can also call help(sum). This will provide the description of the function, how it is to be used, and the arguments.

In the case of sum(), the ellipses . . . represent an unlimited number of numeric elements. sum() also takes the argument na.rm. This is a logical (TRUE/FALSE) argument specifying if NA values (missing data) should be removed when the argument is evaluated.

The function is.function() will check if an argument is a function in R. If it is a function, it will print TRUE to the console.

# confirm that sum is a function

is.function(sum)

## [1] TRUE

# sum takes an unlimited number (. . .) of numeric elements

sum(3, 4, 5, 6, 7)

## [1] 25

# evaluating a sum with missing values will return NA

sum(3, 4, NA)

## [1] NA

# but setting the argument na.rm to TRUE will remove the NA

sum(3, 4, na.rm = TRUE)

## [1] 7Functions can be nested within each other. For example, sqrt() takes the square root of the number provided in the function call. Therefore you can run sum(sqrt(9), 4) to take the sum of the square root of 9 (3) and add it to 4. Or you could write the quadratic formula: [(-b) + sqrt((b^2) - 4ac)] / (2*a).

The View() function

Use this to open a tab in the Script Pane (upper left) to view your data. I use this all the time. You can also click on the variable name in the Environment Pane (upper right) to do the same thing.

myDogs <- data.frame("breed" = c("beagle", "pug", "chihuahua")

, "shedding" = c("moderate", "high", "low"))

View(myDogs)The str() function

Type ?str into the console to read the description of the str function. You can call str() on an R object to compactly display information about it, including the data type, the number of elements, and a printout of the first few elements. We are going to use str in the following sections to investigate R objects, vectors, and data types.

# using str on a function will tell you what arguments it takes

str(sum)

# using str on an R object will give you information about that objectThe c() function

Another important function is c() which will combine arguments to form a vector (more on vectors below). In some programs, such as Excel, this is called concatenation. If you read the help files for c() by calling help(c), you can see that it takes an unlimited . . . number of arguments.

# use c() to combine three numbers into a vector, myFives

myFives <- c(5, 10, 15)

# call str() to see that myFives is a numeric vector of length 3

str(myFives)

## num [1:3] 5 10 15

# adding 5 will operate on each element of the vector. More on vectors below.

myFives + 5

## [1] 10 15 20Vectors

Everything you manipulate in R is called an object. An object has a class, explained below. Vectors are the most basic type of object.

# create a vector of consecutive numbers 1-5

my_vector <- c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

# call `str()` to see myVector is a numeric vector of length 5

str(my_vector)

## num [1:5] 1 2 3 4 5

# Create a random sample of 5000 numbers between 1 and 2 million

my_long_vector <- sample(1:2000000, 5000)

# Evaluating this in the console will fill up your screen

print(my_long_vector)

# However, running View() on this vector fills the header with garbage

View(my_long_vector)

# Run it like this, where you coerce it to a data frame only for viewing purposes.

View(as.data.frame(my_long_vector))

# You can remove an object by calling rm()

rm(my_long_vector)

# Remove multiple items like this:

rm(list =c("my_long_vector", "my_vector"))

# Remove everything

rm(list = ls())Data types (type)

A vector is a sequence of elements of the same type. Vectors can only contain “homogenous” data–in other words, all data must be of the same type. The type of a vector determines what kind of analysis you can do on it. For example, you can perform mathematical operations on numeric objects, but not on character objects. Below I will briefly review some of the data types in R and their type. You can call the class() function on an R object to find out it’s type. For example, running class(sum) will tell you that sum() is a function.

- Numeric or integer

# create a vector of consecutive numbers 1-10 using the colon

my_integers <- c(1:10)

class(my_integers)

## [1] "integer"- Character

# create a vector of book titles. Even though 1984 is composed of numbers, putting it in quotation marks makes it a character string

my_characters <- c("Macbeth", "Dracula", "1984")

class(my_characters)

## [1] "character"

# how many elements in this vector?

length(my_characters)

## [1] 3- Logical (binary

TRUE/FALSE)

# create a logical vector

my_logical <- c(TRUE, FALSE, FALSE, TRUE)

# you can also use the is.logical (or is.character, is.numeric) to verify an object's class

is.logical(my_logical)

## [1] TRUE

# you can also create logical vectors to use as an index

x <- c(2, 4, 8, 5, 1)

# create an index of TRUE/FALSE values where x is greater than 2

my_index <- x > 2

print(my_index)

## [1] FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE

# subset x using that `my_index` in brackets (more on this later)

x[my_index]

## [1] 4 8 5- Factors

- unordered (nominal)

# create a vector of type factor of item formats

my_nominal_factor <- factor(c("book","dissertation", "journal", "book", "dissertation"))

# print a table of the number of items in each format

table(my_nominal_factor)

## my_nominal_factor

## book dissertation journal

## 2 2 1 + ordered (ordinal)# create a vector of type factor of sizes

my_ordinal_factor <- c("small", "medium", "large", "small", "large")

# use the `ordered` function to specify the levels from small to medium to large. Notice that `levels` is an argument of `ordered`

my_ordinal_factor <- ordered(my_ordinal_factor

, levels = c("small", "medium", "large"))

# R now recognizes that small is smaller than medium, which is smaller than large

my_ordinal_factor

## [1] small medium large small large

## Levels: small < medium < largeIf you mix different objects in one vector, R will coerce the vector to be a single class. You can also coerce a vector to be a specific data type. This comes in handy when dealing with ISBNs, which are numeric, but we treat them as characters because we would never perform mathematical operations on them. Coerce data frames by using as.character or as.numeric, for example.

# create a vector of consecutive numbers 1-5

my_mixed_vector <- c(1:10, "a")

my_mixed_vector

## [1] "character"

# coerce the vector to an integer. R replaces the "a" with NA because `a` is not an integer

my_coerced_vector <- as.integer(my_mixed_vector)

## Warning message:

## NAs introduced by coercion

print(my_coerced_vector)

## [1] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 NAMissing values

If our data is missing values, we can use NA to represent those. R functions have special actions when they encounter NA. How you deal with missing data in your analysis is a decision you will have to make–do you remove it entirely? Do you replace it with zeros? That will depend on your own methodological questions.

You can use is.na() to test if a value is NA or not. Conversely, use complete.cases() to test if a value is not missing.

# this expression has some nesting. I am creating a vector combining a sample of 5 letters `` and a repetition of NA five times `rep(NA, 5)`

my_nas <- c(letters[1:5], rep(NA, 5))

print(my_nas)

## [1] "a" "b" "c" "d" "e" NA NA NA NA NA

# Which values are NA?

is.na(my_nas)

## [1] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE

# Which values are complete?

complete.cases(my_nas)

## [1] TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

# How many of each?

table(is.na(my_nas))

## FALSE TRUE

## 5 5

# use the brackets to subset the data and include complete cases only (more on this later)

my_completes <- my_nas[complete.cases(my_nas)]

print(my_completes)

## [1] "h" "k" "y" "w" "q"Helpful functions to provide information about vectors:

length(): number of elements in the vector): returns the data typestr(): compactly displays infomration about the vectoris.logical(),is.numeric(),is.character(), etc. : verifies the data type (TRUE or FALSE)as.logical(),as.numeric(),as.character(), etc. : coerces the vector from one data type to anotheris.na()orcomplete.cases(): returns logical (TRUE/FALSE) vector of values that are NA or, conversely, that are complete

TRY IT YOURSELF

- Assign the sum of 20 and 40 to variable

mySum - Use

is.function()to check ifaverageis a function. Use it to see ifmeanis a function. - Combine 5, 10, 15, NA into a vector

my_vec - Write an expression to get the average of the numbers in

my_vec. Remove the NA if necessary. - Evaluate the following expressions and look at the return values.

my_numeric <- c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

my_characters <- c("Macbeth", "Dracula", "1984", "Jane Eyre", "Beowulf")

my_logical <- c(TRUE, FALSE, FALSE, TRUE, FALSE)

nchar(my_characters)

table(nchar(my_characters))

nchar("my_characters")

my_numeric + 2

as.numeric(my_logical)

my_numeric + my_logical

my_numeric > 3

my_numeric[my_numeric > 3]

c(my_numeric, NA)

is.na(c(my_numeric, NA))

c(my_numeric, "NA")

is.na(c(my_numeric, "NA"))

my_numeric[my_logical]

my_characters[my_logical]

my_numeric["my_logical"]Subsetting vectors

You can use the brackets to subset a vector. Brackets can take either numeric values (which will correspond to the element in the order it exists in the vector) or logical (T/F) values. You can also use functions such as which(), that return numeric values.

# state.name is a built in vector in R of all U.S. states

state.name

state.name[1]

## [1] "Alabama"

state.name[1:5]

## [1] "Alabama" "Alaska" "Arizona" "Arkansas" "California"

# You must use the `c()` function if you have more than one value

state.name[1, 10, 20]

## Error in state.name[1, 10, 20] : incorrect number of dimensions

state.name[c(1, 10, 20)]

## [1] "Alabama" "Georgia" "Maryland"

# There's only one state called Alabama

table(state.name == "Alabama")

## FALSE TRUE

## 49 1

# create a logical vector of state names where "Alabama" == TRUE. Notice you have to use two equals signs.

myAlabamaIndex <- state.name == "Alabama"

myAlabamaIndex

## TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

# subset state.name using that T/F index (will return the only value where myAlabamaIndex == TRUE)

state.name[myAlabamaIndex]

## [1] "Alabama"

# create a logical vector of state names with more than 10 character names

ten_characters <- nchar(state.name) > 10

# you can find out which elements are TRUE values by using the `which()` function

which(ten_characters)

# subset state.names using `which()`

ten_character_state.names <- state.name[ten_characters]

ten_character_state.names

## [1] "Connecticut" "Massachusetts" "Mississippi" "New Hampshire" "North Carolina" "North Dakota" "Pennsylvania"

## [8] "Rhode Island" "South Carolina" "South Dakota" "West Virginia" TRY IT YOURSELF

- Subset

state.nameto include only element number 25. What state is element 25? - Subset

state.nameto include elements 3, 12, and 40. You will need to use thec()function. - Alabama is element number 1. What element number is New York?

- Use the

table()and thenchar()functions to find out how many state names have more than 7 characters. - Create a vector of only these states.

Data frames

A data frame is the term in R for a spreadsheet style of data: a grid of rows and columns. The number of columns and rows is virtually unlimited, but each column must be a vector of the same length. A dataframe can comprise heterogeneous data: in other words, each column can be a different data type. However, because a column is a vector, it has to be a single data type.

Create a data frame

You will likely be importing your dataset, but it is easy to create a data frames on your own:

# create three vectors

title <- c("Macbeth","Dracula","1984")

author <- c("Shakespeare","Stoker","Orwell")

checkouts <- c(25, 15, 18)

available <- c(TRUE, FALSE, FALSE)

# create a data frame using the data.frame() function. Specify stringsAsFactors as FALSE

ebooks <- data.frame(title, author, checkouts, stringsAsFactors = F)You can print small data frames like this to the console using print(ebooks)

title author checkouts

1 Macbeth Shakespeare 25

2 Dracula Stoker 15

3 1984 Orwell 18But for larger data frames, it’s best to use the View() function: View(ebooks). You can also use head() to see a preview (in this particular case, the data frame is too small to preview).

All you Excel users might be wondering: how do I click in a cell and edit it?! R doesn’t work like that. If you want to manipulate values, it’s best to do it with an expression in the R console, and have all modifications documented in your script. We will be going into how to do these modifications next session. But if you insist, you can pull up a traditional point-and-click spreadsheet by using the edit() function: edit(ebooks).

Exploring data frames

There are a number of ways to explore your data frame:

#display information about the data frame

str(ebooks)

# dimensions: 3 rows, 3 columns

dim(ebooks)

## [1] 3 3

# number of rows

nrow(ebooks)

## [1] 3

# number of columns

ncol(ebooks)

## [1] 3

# column names

names(ebooks)

## [1] "title" "author" "checkouts"You can use the $ symbol to work with particular variables.

print(ebooks$title)

class(ebooks$title)

## [1] "character"

class(ebooks$checkouts)

## [1] "numeric"

# use summary() for more detail on a variable

summary(ebooks$checkouts)

## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

## 15.00 16.50 18.00 19.33 21.50 25.00 TRY IT YOURSELF

- Look at the help file for

state.name - Manually construct three vectors:

stateName,division, andarea. - Use

data.frame()to create a data frame of these three vectors. Assign it tomyStates. Remember to setstringsAsFactorstoFALSE - What is the

)of each vector? - Using the

$character, runsum()on theareavariable. What is the sum area of these five states? What is the median?